Overview

Ethnographic mapping moves beyond the idea of space as a neutral or purely physical representation of the world. It brings to the fore the lived experiences, memories, and meanings that people assign to their environments, transforming abstract spaces into meaningful places. Through mapping practices grounded in ethnographic engagement, researchers trace how social life unfolds across landscapes, rooms, and everyday pathways. This tool invites such interpretive mapping by allowing users to add annotations and fieldnotes directly onto maps—whether a global map or a custom image such as a floor plan or architectural drawing—thereby visualizing the intersection of spatial form and lived experience.

There are two versions of the tool. One uses an interactive world map and the other one allows you to upload the image of a floor plan, architectural drawing, custome map, or any other image.

An example of the tool in use

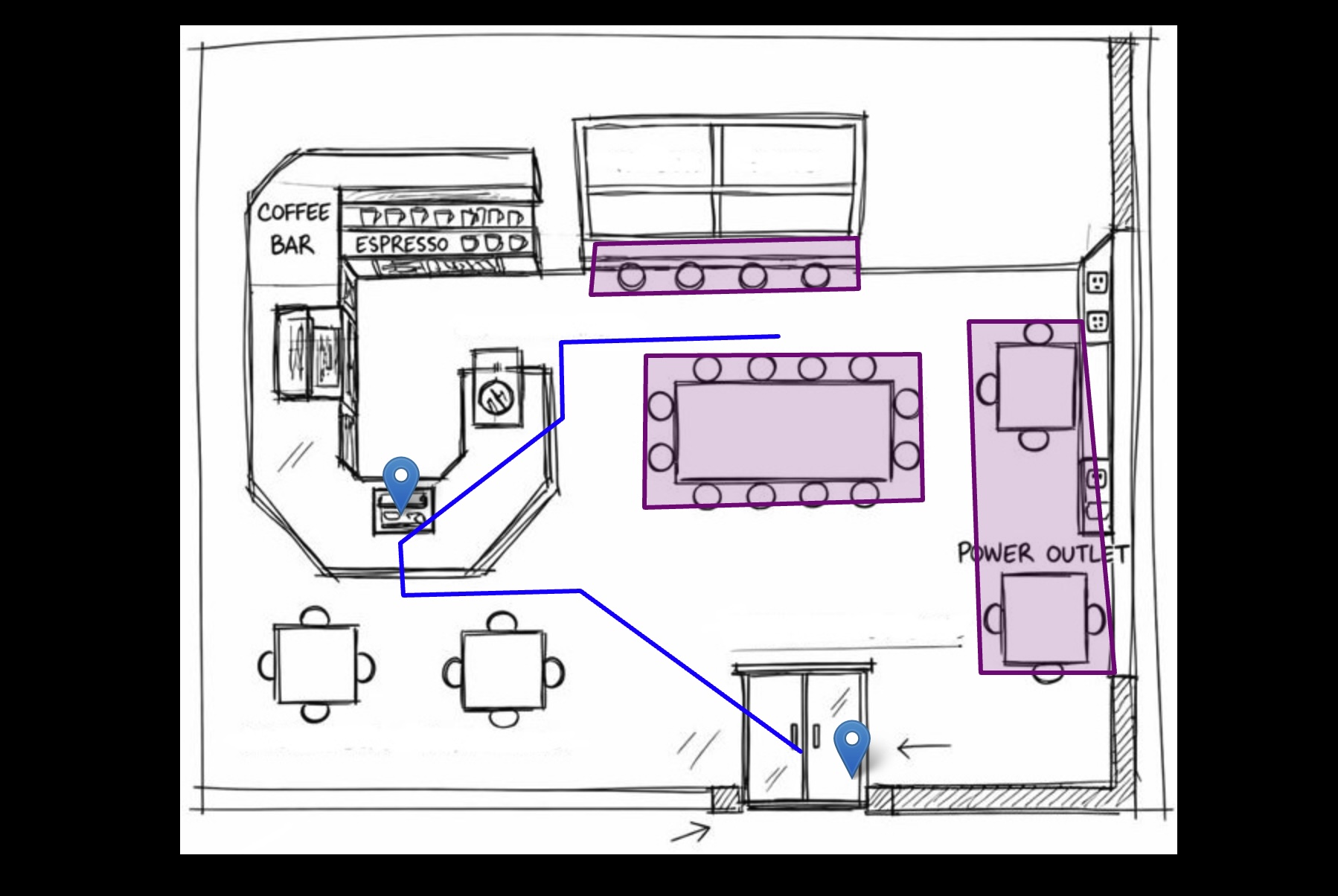

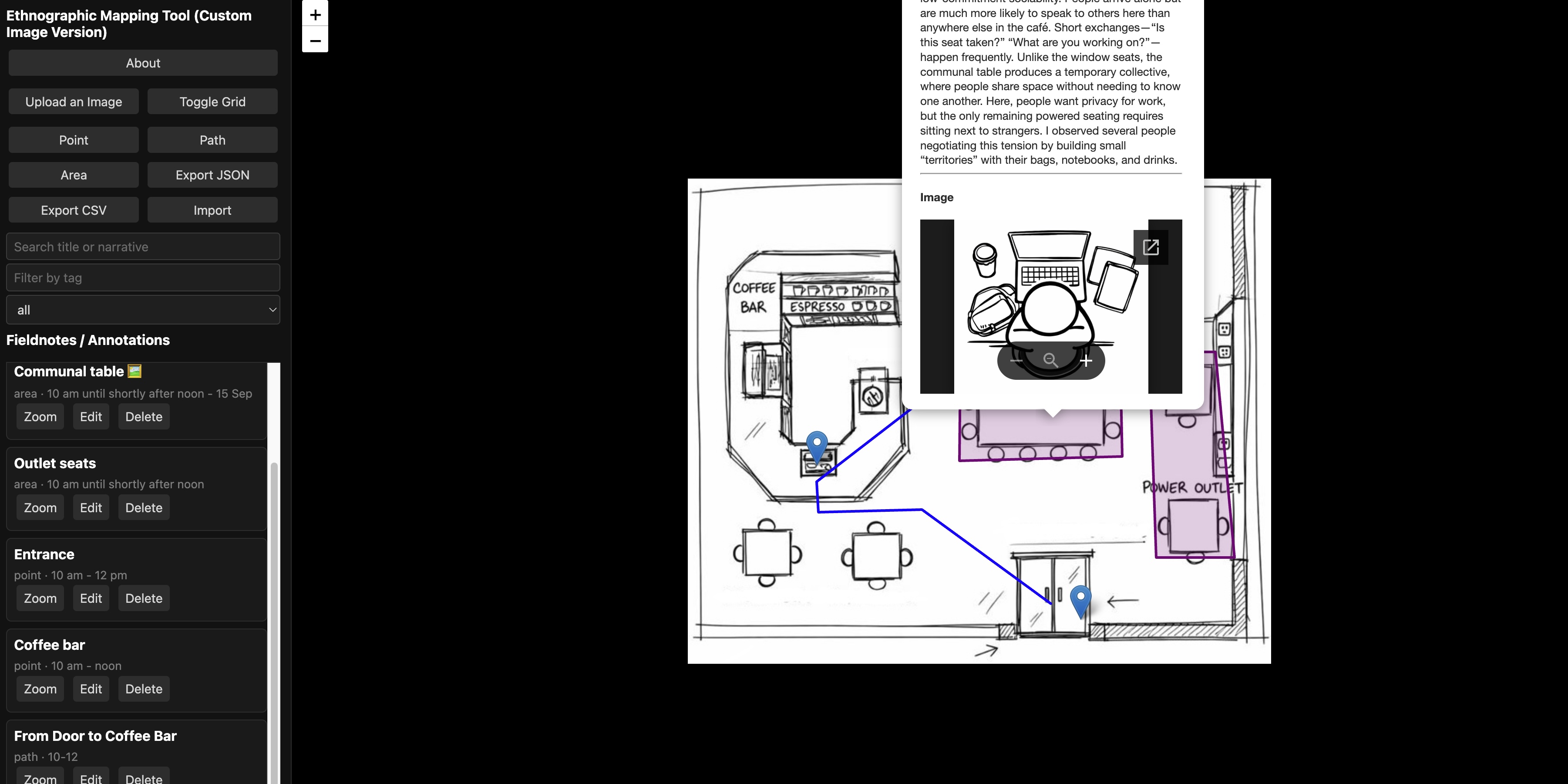

The following analysis illustrates how the tool can be used to analyze and visualize socia and spatial dynamics in a coffee shop. To view and interact with the map, please download (1) this floor plan sketch and (2) this file containing the annotation data, open the custom image of the ethnographic mapping, click Upload an Image, and select the floor plan you just downlooaded. Then, click Load JSON, and select the annotation file you downloaded. The map should then open. Below are a few screenshots illustrating what you will see.

Using Annotated Spatial Maps to Analyze Social Life in a Coffee Shop

In this example, a student conducted participant-observation in a small independent coffee shop and used the Architectural Plan Annotation Tool to upload a hand-drawn floor plan of the space. Rather than treating the map as a neutral background, the student used it as an analytic surface on which observations, images, and interpretations could accumulate.

During observation, the student created spatially anchored fieldnotes directly on the map. These notes were later edited and summarized for the current example. Window seats were tagged as a distinct area, where notes described people working in isolation while being visually exposed to the street. By placing these notes directly on the drawn window zone, a pattern became visible that would have been harder to see in a linear notebook: openness and visibility coincided with guarded, inward-focused behavior. The spatial annotation made it possible to see that “isolation” was not simply an individual preference but something produced by where bodies were placed in relation to light, glass, and the gaze of others.

Similarly, the communal table was marked as a separate area, with notes attached (later edited and shortened for this example) documenting short conversations between strangers, subtle negotiations over space, and the tension between wanting to work privately and being forced into proximity by the availability of power outlets. When these notes were layered on the same map as sketches of laptops, backpacks, and coffee cups, the student could visually trace how people built small “territories” around themselves. The overhead, digital drawing of personal belongings did not simply illustrate the scene; it revealed how objects functioned as boundaries, pushing others away while allowing people to remain seated in a shared space.

Paths were also annotated. The repeated movement from the entrance to the coffee bar and then toward outlet-rich areas showed how infrastructure quietly shaped the flow of bodies through the café. Seeing these paths overlaid on the floor plan allowed the student to connect movement patterns to broader questions about productivity, scarcity, and competition in café culture.

What the tool made possible was not just better documentation but a different kind of analysis. Notes, sketches, and spatial relations remained in dialogue with one another. Instead of translating lived experience into abstract prose first and only later trying to remember where things happened, the student’s analytic process unfolded directly on the map. The café emerged as a social system composed of people, furniture, electricity, windows, and norms of behavior—all interacting in ways that could be seen, not just described.

By keeping fieldnotes, drawings, photos, and spatial layouts in one annotated environment, the tool allows students to notice patterns they might otherwise miss: how isolation clusters in one corner, how sociability gathers around certain tables, how power outlets quietly organize time and occupancy. The map becomes a thinking surface—a way of doing ethnography that is not only written but spatial, visual, and relational.